FAQ – What are the phenomena associated with air humidity?

Dry air and dehumidification processes

Condensation

The amount of water vapour that can be retained in the air depends on the air temperature (for a given atmospheric pressure). Warm air can therefore contain a higher mass of water than cold air. For a given amount of water vapour in the air, there is a cooling limit below which the temperature cannot fall without causing condensation. The most typical example is morning dew after a cool night following a sunny day. The cooling air cannot retain the water vapour it previously contained. Air that has reached this critical temperature is then saturated with moisture. It now holds 100% of the moisture it is capable of containing: this is the dew point. When the air has not yet reached its dew point, the amount of water it contains is expressed as a percentage of the water it would contain if it were fully saturated. This is called relative humidity.

Example: the air in a specific area is 25°C and contains 10 grams of water per kilogram of dry air. The relative humidity of this air is around 50%, meaning it can still hold twice as much water vapour. If this air is heated from 25°C to 32°C, its relative humidity will drop to around 33%, while the actual amount of water remains the same, because air at 32°C can hold up to about 30 grams of water per kilogram of dry air.

On the contrary, if this air is cooled to 14°C, condensation will inevitably occur. This also means that condensation would form on any surface or piece of equipment whose surface temperature is below 14°C, if located in a space containing 10 grams of water per kilogram of dry air—regardless of the air temperature in that space.

Learn more about: Preventing condensation in industrial buildings

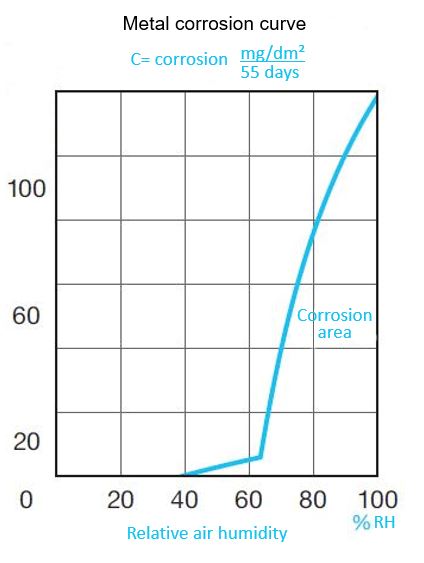

Corrosion

Air humidity does not need to reach condensation levels to cause damage. Even moist air alone can corrode metals. In fact, for electrochemical corrosion to occur on metals exposed to air, several conditions must be met:

• A potential difference between pure and impure areas on the surface of the metal,

• The presence of oxygen,

• The presence of water.

This creates an electrolytic environment that can only be eliminated if one of these three factors is removed. However, in most cases, it is not possible to eliminate oxygen or remove surface impurities. Ultimately, it is by controlling the relative humidity of the air that corrosion can be reduced and even eliminated. This diagram illustrates how the corrosion coefficient of steel varies with the relative humidity of the air. It indicates that this corrosion coefficient does not vary proportionally with ambient humidity. At 60% RH, the curve drops sharply, and at 35% RH it tends towards zero. Below 35% RH, corrosion becomes impossible.

Discover how our solutions help combat corrosion in the shipbuilding industry

Corrosion also depends on temperature and increases with it. Below –2°C, it becomes negligible. Air pollution also has a significant influence on corrosion phenomena. In some cases, the temperature of the metal wall may differ from that of the ambient air. When the wall temperature is lower than the air temperature, the relative humidity of the ambient air must be kept lower to ensure that the air in contact with the wall remains below 60%. Example: to ensure a relative humidity of 60% for the air in contact with a wall at 10 °C, the ambient relative humidity must be kept at 45% when the room temperature is 15 °C.

Learn more about: Dehumidifying the air to combat corrosion

Discover the Map of humidity and climates in France, an essential tool for air dehumidification

The transfer of water vapour (humidification or drying)

The moisture content in a product is defined as the ratio of the mass of water it contains to the mass of dry matter. This quantity is referred to as the product’s specific moisture content. When the product is in a given environment, if its partial water vapour pressure is higher than that of the air, water vapour is transferred from the product to the air, causing the product to dry. In the opposite case, the product is humidified. Conversely, if the partial water vapour pressure of the product is lower than that of the air, the product absorbs moisture and becomes humidified. This determines the sorption curves that reflect the thermodynamic equilibrium between the moist product and the surrounding atmosphere. These curves are most often represented at constant temperature (sorption isotherm). Depending on whether equilibrium is reached by adsorption (humidification) or desorption (drying), the curve is slightly different (hysteresis phenomenon). Additionally, the equilibrium moisture content decreases as the temperature increases.

Water in moist products is composed of:

- unbound water, sometimes called surface water as it lies in the macropores of the product or its outer surface. This water applies a vapour pressure equal to the saturated vapour pressure at the given temperature.

- Bound water, which corresponds to water adsorbed on the inner surface of the porous material in one or more layers (physisorption phenomenon), and water retained by capillarity in the finest pores of the material. This water, which is the most difficult to remove, applies a vapour pressure lower than the saturated vapour pressure at the given temperature.

- Chemically bound water, also known as water of crystallisation, which remains during the drying process. Equilibrium moisture content corresponds to the humidity level at which a product can be dried with an air of specific thermodynamic characteristics.

Read our article: The humid air diagram, also known as psychrometric chart, is an essential tool in climate engineering and thermodynamics.